Introduction: Why Festivals Were Central to Life in Ancient Egypt

Festivals in Ancient Egypt, festivals were not mere moments of joy or public entertainment. They were deeply embedded in the spiritual, political, and agricultural fabric of society. For the ancient Egyptians, celebrating a festival was an act of devotion and responsibility—one that helped maintain the delicate balance of the universe itself.

At the core of Egyptian belief stood Ma’at, the sacred concept that governed order, truth, justice, and harmony. Egyptians believed that without constant ritual attention, this balance could collapse, inviting chaos and divine displeasure. Festivals, therefore, were not optional traditions but vital mechanisms through which humans cooperated with the gods to sustain cosmic stability.

This worldview explains why the Egyptian calendar was densely filled with religious festivals. Nearly every phase of life—farming cycles, royal events, celestial movements, and divine myths—was marked by a sacred celebration designed to reinforce harmony between the earthly and divine realms.

Kahire Turu 2026 – Hurgada’dan Kahire ve Giza Piramitleri Ziyareti –Luxor Turu 2026 – Hurghada’dan Tarih ve Nil Macerası

The Origins of Organized Festivals in Ancient Egypt

Historical records and archaeological discoveries suggest that Egypt’s earliest rulers played a decisive role in shaping religious festivals. During the Early Dynastic Period, when Upper and Lower Egypt were unified under King Narmer around 3100 BCE, religious celebrations became standardized across the kingdom.

This unification was not only political; it was profoundly spiritual. By organizing festivals on fixed dates and aligning rituals across regions, early pharaohs aimed to unify belief systems and reinforce Ma’at on a national scale. Temples became centers of ritual authority, and festivals evolved into state-sponsored events that bound the population to both the gods and the ruling elite.

Religion, in this sense, functioned as the invisible thread holding Egyptian civilization together.

The Pharaoh’s Sacred Role in Religious Festivals

The pharaoh was not simply a ruler; he was the living intermediary between gods and humans. His involvement in festivals was essential, as each ceremony reaffirmed his divine legitimacy and cosmic responsibility.

During major festivals, the pharaoh was expected to:

- Declare and regulate festival dates based on religious and astronomical calculations

- Finance temple ceremonies, offerings, and priesthood activities

- Participate symbolically or physically in sacred rituals

Through these acts, festivals reinforced royal authority. A successful celebration signaled divine approval, prosperity, and continued order. In contrast, failed rituals or disrupted festivals were interpreted as ominous warnings of imbalance or divine dissatisfaction.

The Festival of the Nile Inundation (Wafā’ al-Nil)

Cultural and Historical Importance

Among all Egyptian festivals, few carried greater significance than the Festival of the Nile Inundation. This annual celebration coincided with the arrival of the Nile’s floodwaters, marking the beginning of Akhet—the season of inundation.

The flooding of the Nile was the lifeblood of Egypt. It renewed the soil, ensured agricultural productivity, and sustained the economy. To the ancient Egyptians, this event was not a natural coincidence but a divine act—clear evidence that the gods continued to favor Egypt.

A successful inundation meant abundance, stability, and survival. A weak or excessive flood, however, threatened famine and destruction. This uncertainty made the festival both a celebration and a plea for divine mercy.

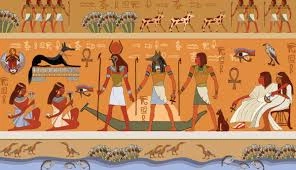

Hapy: The Divine Source of Fertility and Abundance

Central to the Festival of the Nile was Hapy, the god personifying the Nile’s life-giving power. Unlike warrior gods or royal deities, Hapy was depicted with a full, nurturing body—symbolizing fertility, nourishment, and generosity.

Honoring Hapy was a spiritual necessity. Egyptians prayed for a flood that was:

- Strong enough to fertilize the land

- Gentle enough to avoid devastation

- Perfectly balanced to sustain life

This ideal moderation reflected the Egyptian obsession with harmony and balance, reinforcing the philosophy of Ma’at in both nature and society.

Rituals and Ceremonies of the Nile Festival

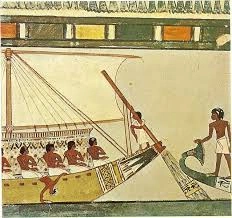

Sacred Processions Along the River

One of the most awe-inspiring aspects of the festival was the procession of sacred statues along the Nile. Divine images were placed on ceremonial boats and escorted by priests, musicians, and singers. The river itself became a floating sanctuary, transforming the landscape into a living temple.

Offerings to the Gods

Offerings formed the heart of the celebration and typically included:

- Fresh flowers symbolizing renewal and rebirth

- Agricultural produce representing prosperity

- Bread and beer, staples of daily Egyptian life

- Incense and aromatic oils believed to please the gods

These offerings were acts of gratitude as well as spiritual negotiations—requests for continued fertility and protection.

Hymns and Sacred Prayers

Throughout the festival, hymns were recited in praise of Hapy and the Nile. These prayers asked for fertile fields, abundant harvests, and divine guardianship over Egypt. Music, rhythm, and poetic language amplified the spiritual intensity of the celebration, uniting the community in shared devotion

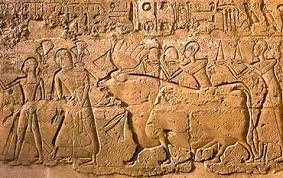

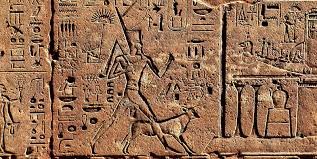

Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Egyptian Festivals

The story of ancient Egyptian festivals is not confined to papyrus texts or temple inscriptions alone. It is permanently etched into stone, carved across the walls of monumental sanctuaries that still stand today. These archaeological remains provide some of the most compelling evidence of how deeply festivals were woven into the religious and social life of ancient Egypt.

Temple reliefs functioned as more than decoration; they were visual records meant to preserve sacred actions for eternity. Through them, modern scholars can reconstruct the rhythm, scale, and meaning of festivals that once shaped the spiritual calendar of the Nile Valley.

Among the most significant sites preserving festival imagery are:

- The Karnak Temple Complex (Luxor)

- The Temple of Edfu

- Philae Tapınağı

The reliefs found at these locations depict ceremonial river processions, priests presenting offerings to the gods, musicians performing sacred chants, and complex ritual sequences involving both clergy and royal figures. Together, these scenes reveal that festivals were not abstract theological ideas but large-scale public events involving temples, cities, and entire communities.

They offer a rare glimpse into lived religion—how faith was practiced, seen, and experienced by ordinary Egyptians alongside kings and priests.

Cultural Legacy: Does the Nile Festival Still Exist?

Although the original religious structure of the Nile Inundation Festival gradually faded following profound religious, political, and cultural transformations, its essence never disappeared. Instead, it adapted and survived within Egypt’s collective memory.

This legacy endures today in a symbolic observance known as Wafā’ al-Nil, meaning “The Faithfulness of the Nile.” While no longer practiced as an ancient religious ritual, the celebration reflects an unbroken emotional and cultural bond between Egyptians and the river that sustained their civilization for millennia.

The Nile remains a symbol of life, fertility, and continuity. Modern reverence for the river echoes beliefs that date back to the age of the pharaohs, demonstrating how deeply ancient traditions continue to influence Egyptian identity.

The Opet Festival: Power, Religion, and Kingship in Ancient Thebes

Among the grand festivals of ancient Egypt, few rivaled the political and religious importance of the Opet Festivali. Celebrated in Thebes—modern-day Luxor—during the New Kingdom, Opet flourished especially under the reigns of Queen Hatshepsut and King Amenhotep III.

The festival was dedicated primarily to Amun, the supreme god of Thebes, and took place within a city that served as the spiritual heart of Egypt. Over time, Opet became a cornerstone of state ideology, blending divine worship with royal authority.

Purpose of the Opet Festival

At its core, the Opet Festival existed to renew the king’s divine legitimacy. Through a carefully structured series of rituals, the pharaoh was symbolically reborn as Egypt’s rightful ruler, reaffirmed by the will of Amun himself.

The festival emphasized that kingship was not inherited by blood alone but sustained through divine approval. In this context, the pharaoh functioned as both a political leader and a sacred figure entrusted with maintaining Ma’at—the universal principle of balance, justice, and order.

Beyond its theological role, the Opet Festival also served a powerful political purpose. It displayed the wealth, stability, and organizational strength of the Egyptian state, reinforcing loyalty among the population and affirming the authority of the ruling dynasty.

Rituals and Celebrations of the Opet Festival

The Sacred Procession Along the Avenue of the Sphinxes

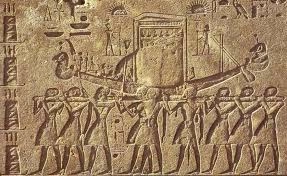

The most dramatic moment of the Opet Festival was the grand procession that traveled from Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple along the legendary Avenue of the Sphinxes. Sacred statues of the Theban Triad—Amun, Mut, and Khonsu—were carried in ceremonial barques, accompanied by priests, musicians, and officials.

Each deity embodied a fundamental cosmic force:

- Amun represented supreme divine authority

- Mut symbolized motherhood and royal protection

- Khonsu governed time, renewal, and cosmic balance

This symbolic journey signified the transfer and renewal of divine power, ensuring harmony between the gods, the king, and the land of Egypt.

Archaeological Depictions of the Opet Festival

Some of the most detailed visual records of the Opet Festival survive on the walls of Karnak and Luxor Temples. These reliefs illustrate:

- Processional parades moving through the city

- Priestly rituals performed before the gods

- Musical performances involving singers and instrumentalists

- Active participation of the general population

Such imagery confirms that Opet was not a closed royal ceremony. It was a city-wide event that blurred the boundaries between temple, palace, and everyday life, uniting religion, politics, and society into a single sacred experience.

Historical Importance of the Opet Festival

The Opet Festival stands as a powerful example of how ancient Egypt fused faith with governance. Through this celebration, religious belief was transformed into political stability, and divine mythology became a tool for maintaining order across the kingdom.

Its success required advanced planning, vast resources, and a highly organized priesthood—clear evidence of the sophistication of Egyptian civilization. More importantly, Opet embodied the principle of Ma’at, demonstrating that Egypt was governed not by chance or chaos, but by a carefully preserved cosmic balance.

Through festivals such as Opet, ancient Egypt expressed its deepest values—order over disorder, continuity over disruption, and harmony between the human and divine worlds

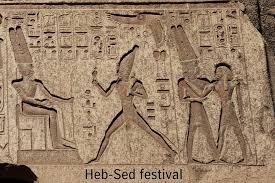

The Heb-Sed Festival: Renewing Royal Power in Ancient Egypt

Among the most remarkable royal traditions of ancient Egypt stands the Heb-Sed Festival, also known as the Sed Festival. Unlike ceremonies that marked the beginning of a reign, this unique celebration focused on renewal—reviving the king’s authority, vitality, and divine legitimacy after many years on the throne.

Traditionally held after approximately thirty years of rule, the Heb-Sed Festival symbolized a moment of transformation. It was believed to restore the pharaoh’s strength, reaffirm his sacred bond with the gods, and reestablish cosmic balance. In essence, the festival functioned as a ritual rebirth of kingship itself.

As one of the earliest documented royal ceremonies in Egyptian history, the Heb-Sed Festival reflects the deep connection between political authority, religion, and the concept of Ma’at—the universal order that sustained the world.

Origins and Purpose of the Heb-Sed Festival

The earliest known reference to the Heb-Sed Festival dates back to King Den of the First Dynasty, highlighting its foundational role in the ideology of Egyptian kingship from the very beginning of the state.

The festival served several interconnected purposes:

- To symbolically restore the pharaoh’s physical vitality after decades of rule

- To publicly reaffirm his divine right to govern before priests, officials, and the population

- To ensure the continuation of Ma’at through sacred royal performance

In the Egyptian worldview, the king was not merely a ruler but a cosmic pillar. Any sign of weakness in the pharaoh threatened political stability and, more importantly, the balance of the universe. The Heb-Sed Festival was therefore a sacred obligation—essential for the survival of Egypt itself.

Rituals and Ceremonies of the Heb-Sed Festival

The Pharaoh’s Symbolic Run

One of the most iconic elements of the Heb-Sed Festival was the ritual run. During this ceremony, the pharaoh moved—walking or running—along a designated sacred course within a ceremonial enclosure.

This act carried profound symbolism. It demonstrated the king’s physical capability to rule and his continued mastery over the land of Egypt. More than a display of strength, the run represented renewal, motion, and readiness to govern for another cycle of time.

To the audience, the message was unmistakable:

the king remained fit—both physically and spiritually—to lead and protect the nation.

Rituals of Rejuvenation and Divine Renewal

Beyond physical display, the festival included ceremonies aimed at restoring youth, vitality, and divine favor. Symbols of fertility, rebirth, and strength played a central role, reinforcing the idea that kingship itself could be renewed through ritual.

Temple reliefs often depict gods transferring sacred energy directly to the pharaoh, emphasizing that renewal was granted by divine will. Through these acts, the king was not simply confirmed in power—he was transformed, reborn as a renewed embodiment of divine authority.

Archaeological Evidence of the Heb-Sed Festival

Material evidence of the Heb-Sed Festival survives at several important archaeological sites, offering valuable insight into its ceremonial complexity:

- The Step Pyramid Complex of Djoser at Saqqara

- Royal temple complexes at Abusir

Reliefs and architectural features from these locations portray the pharaoh in ritual postures, accompanied by priests and attendants. The scenes emphasize movement, ceremony, and physical vitality—visual affirmations of restored power and legitimacy.

These depictions confirm that the Heb-Sed Festival was not symbolic in theory alone; it was physically enacted, carefully staged, and publicly witnessed.

Historical and Cultural Significance of the Heb-Sed Festival

The Heb-Sed Festival reveals a core principle of ancient Egyptian governance:

royal power was not permanent—it had to be continually renewed.

By ritually restoring the pharaoh’s strength, Egyptians believed they were safeguarding the stability of the state, maintaining divine favor, and preserving the harmony of the cosmos. The king stood at the center of this balance, acting as the living bridge between humanity and the gods.

Through the Heb-Sed Festival, ancient Egypt expressed a profound understanding of leadership—one rooted not only in authority, but in renewal, responsibility, and cosmic harmony. It remains one of the clearest examples of how ritual, belief, and political power were inseparably intertwined in one of history’s greatest civilizations.

Cosmic Renewal and the Sacred Cycle of Time in Ancient Egypt

In the ancient Egyptian worldview, time was not linear but cyclical, moving through repeating phases of creation, decay, and renewal. Certain festivals were designed to mark these transitions between cosmic cycles, ensuring that life, harmony, and divine order would continue uninterrupted.

Celebrations dedicated to the births of sacred deities played a decisive role in closing one cosmic year and inaugurating the next. Through carefully timed rituals, the Egyptians believed they were actively participating in the renewal of the universe. These festivals were acts of cosmic maintenance—meant to secure abundance, vitality, and balance for the land and its people in the year ahead.

At the heart of this belief stood Ma’at, the universal law governing order, balance, and truth. Every ritual, hymn, and offering served to reaffirm this principle, reminding humans of their responsibility in sustaining cosmic harmony.

Cultural Continuity: Does This Sacred Cycle Still Exist?

Although the original ceremonial frameworks gradually faded with the passage of centuries, their essence never vanished. Instead, these ancient ideas became woven into Egypt’s cultural memory.

Modern traditions associated with the Nile, seasonal transitions, and astronomical observations still echo these early beliefs. Even without their original religious structure, the symbolic connection between nature, time, and renewal remains deeply rooted in Egyptian consciousness. In this way, the past continues to resonate within the present, preserving an unbroken dialogue between ancient ritual and contemporary life.

The Egyptian New Year Festival (Wepet Renpet)

Importance of the Festival

Bu Wepet Renpet Festival, meaning “The Opening of the Year,” marked the ancient Egyptian New Year and stood among the most significant events in the religious calendar. Its timing was determined by a precise astronomical event: the heliacal rising of the star Sirius.

This celestial phenomenon occurred just before the annual flooding of the Nile, making it a powerful omen of renewal and fertility. For the Egyptians, the appearance of Sirius was not a coincidence of the heavens—it was a divine signal announcing rebirth, prosperity, and the return of life to the land.

The New Year was therefore not a simple change of date, but a sacred moment when the cosmos, the Nile, and human society aligned.

Purpose of the Egyptian New Year Celebration

The central purpose of Wepet Renpet was to restore harmony between heaven and earth. By aligning stellar movements with agricultural cycles and ritual practices, the Egyptians sought to:

- Secure fertile soil and abundant harvests

- Ensure divine favor for both the pharaoh and the people

- Renew cosmic balance for the year to come

The New Year functioned as a spiritual reset—a moment when chaos was symbolically pushed aside and order was reaffirmed across the universe.

Rituals and Ceremonies of Wepet Renpet

The celebration involved a series of sacred acts designed to prepare the world for renewal:

- Purification rituals, cleansing temples and sacred spaces to welcome renewed divine presence

- Offerings and sacrifices, presented to the gods as requests for protection and prosperity

- Astronomical rites, emphasizing the sacred role of Sirius in the rebirth of nature and the agricultural cycle

Together, these ceremonies transformed the New Year into a collective experience of hope, anticipation, and sacred renewal shared by the entire society.

The Festival of the Goddess Bastet

Historical Background and Significance

Among the most joyful and emotionally rich festivals of ancient Egypt was the celebration dedicated to Bastet, goddess of joy, love, music, fertility, and domestic protection. The festival took place in Bubastis (modern Tell Basta in the Sharqia Governorate), the principal center of her worship.

Bastet was commonly depicted as a cat or a woman with a feline head—symbols of grace, vigilance, and maternal care. Her festival stood in sharp contrast to formal state ceremonies, offering insight into the emotional and social life of ordinary Egyptians.

Objectives of the Bastet Festival

The celebration fulfilled several spiritual and communal functions:

- Honoring Bastet as protector of households and motherhood

- Encouraging joy, music, dance, and collective celebration

- Strengthening social bonds and shared happiness

- Invoking protection, fertility, and healing

Ancient accounts describe the festival as lively and exuberant, marked by music, dancing, and river processions. It was a moment when everyday people could engage directly with the divine through joy rather than solemn ritual.

Cultural and Social Importance of the Bastet Festival

The Festival of Bastet reveals an often-overlooked aspect of ancient Egyptian civilization:

joy itself was sacred.

By celebrating happiness, music, and love, Egyptians acknowledged that emotional well-being was essential to Ma’at just as much as order and authority. Through Bastet, the divine entered daily life—not as a distant cosmic force, but as a warm, protective presence woven into family, community, and celebration.

This festival reminds us that ancient Egypt was not solely a civilization of monuments and rituals, but also one that deeply valued human emotion, connection, and the sacred power of joy.

Festivities and Ritual Practices of the Bastet Festival

Music, Dance, and the Celebration of Life

Music and dance formed the living soul of the Bastet Festival. From the earliest moments of the celebration, melodies filled the air as musicians played harps, flutes, sistrums, and drums. The rhythm was lively, inviting movement rather than contemplation, joy rather than silence.

Group dances unfolded spontaneously, expressing vitality, freedom, and the simple pleasure of being alive. Unlike the solemn rituals performed within temple walls, these performances were open and emotionally charged. Movement itself became an act of devotion, transforming joy into something sacred.

In ancient Egyptian belief, celebrating life was not a distraction from religion—it was an essential expression of it.

Grand Communal Celebrations

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Bastet Festival was its inclusiveness. Men, women, and children from every social class participated without distinction. Farmers, artisans, merchants, and officials stood side by side, united by shared celebration rather than hierarchy.

Pilgrims traveled to Bubastis by land and by river, often singing and playing music along the way. As boats arrived from across Egypt, the city transformed into a living mosaic of voices, colors, and movement. Streets and waterways became pathways of celebration, creating a rare sense of national unity centered on joy rather than power.

Few ancient religious traditions embraced communal participation on such a scale.

Joyful Merriment and Social Freedom

Food and drink were shared freely throughout the festival, contributing to an atmosphere of openness and exuberance. Ancient accounts emphasize that restraint—so common in formal religious ceremonies—was intentionally relaxed during the celebration of Bastet.

Laughter, music, and social interaction flowed without rigid boundaries. This temporary suspension of formality made the festival deeply beloved by the population, offering a moment when everyday concerns gave way to collective happiness.

The Bastet Festival stood apart within the Egyptian religious calendar precisely because it celebrated emotional freedom as a sacred experience.

Historical Accounts: Herodotus’ Testimony

The Greek historian Herodotus provides one of the most vivid external descriptions of the Bastet Festival. He famously referred to it as:

“The most magnificent and joyous celebration in Egypt.”

According to his observations, attendance could reach hundreds of thousands, making it one of the largest religious gatherings in the ancient world. His testimony highlights not only the immense scale of the festival, but also its powerful emotional impact on those who took part.

Such descriptions confirm that the Bastet Festival was not a marginal event, but a central expression of Egyptian religious and social life.

Cultural and Religious Importance of the Bastet Festival

The Festival of Bastet reveals a deeply human dimension of ancient Egyptian civilization. Alongside monumental temples and royal rituals, Egyptians honored joy, music, femininity, and emotional connection as sacred values.

By venerating Bastet—the goddess of motherhood, protection, and happiness—Egyptians affirmed that emotional well-being and social harmony were essential components of Ma’at. Religion, in this sense, was not rooted solely in fear or obedience, but in beauty, affection, and shared joy.

The divine was present not only in silence and ceremony, but in laughter, music, and community.

Festivals That Endure Through Time

Despite the passage of millennia and the transformation of religions and empires, the essence of many ancient Egyptian festivals has endured. While their names and outward forms evolved, their symbolic core remains deeply embedded in Egypt’s cultural identity.

Sham el-Nessim: A Living Legacy of Ancient Egypt

Considered one of the oldest continuously celebrated festivals in the world, Sham el-Nessim traces its origins to ancient agricultural rituals marking the arrival of spring and the renewal of life.

Modern traditions still echo Pharaonic symbolism, including:

- Family outings to parks and green spaces

- Eating traditional foods such as eggs, salted fish, onions, and lettuce

Each element reflects ancient Egyptian concepts of rebirth, fertility, and vitality—clear evidence that the spirit of the pharaohs continues to shape everyday life in Egypt.

Wafā’ al-Nil: Loyalty to the Eternal River

Reverence for the Nile has never faded. Even today, echoes of the ancient Nile Inundation Festival survive through:

- Regional celebrations centered on the river

- Songs, stories, and cultural imagery honoring its life-giving power

- Social rituals expressing gratitude for its role in survival and prosperity

The Nile remains more than a river—it is a symbol of continuity, identity, and endurance, just as it was in the age of ancient Egypt.

Key Facts at a Glance

Ancient Egyptian festivals were complex, multi-dimensional events that merged religion, politics, nature, and community into a single sacred experience. They were not occasional interruptions to daily life, but an essential rhythm that shaped society itself.

Some festivals extended over several weeks and involved every layer of society—from the pharaoh and priesthood to farmers, craftsmen, and families. Celebration was collective, public, and deeply meaningful.

Temples functioned far beyond their religious role. They acted as administrative hubs that organized food distribution, coordinated entertainment, scheduled public holidays, and managed large-scale gatherings.

During certain historical periods, Egypt observed more than 200 festival days each year, making celebration a core element of daily life rather than a rare exception.

The importance of festivals is evident in how meticulously they were recorded. Detailed depictions appear on temple walls, papyri, and tomb reliefs—especially at major sites such as Karnak, Luxor, Edfu, Dendera, and Saqqara—ensuring that sacred celebrations would be remembered for eternity.

Where Do We Know About These Festivals From?

Our understanding of Pharaonic festivals is drawn from a rich combination of archaeological and textual sources that together form a remarkably detailed picture.

Temple reliefs and inscriptions provide visual narratives of processions, offerings, musicians, priests, and ritual performances, often carved with extraordinary precision.

Tomb paintings reveal the human side of festivals, depicting banquets, dancers, music, and family participation during celebrations such as the Beautiful Feast of the Valley.

Religious texts and ceremonial calendars list feast days, ritual obligations, offerings, and priestly duties, allowing scholars to reconstruct the religious year in detail.

Classical authors, particularly Greek writers like Herodotus, described Egyptian festivals with astonishment. Their accounts emphasize the immense scale, emotional intensity, and joyful atmosphere of these gatherings.

Together, these sources confirm that festivals were central to Egyptian life—not symbolic footnotes, but lived experiences.

Festivals as a Tool of Power

Festivals were not only acts of devotion; they were also powerful instruments of statecraft.

Through public celebration, the divine status of the pharaoh was reaffirmed before the population. Rituals made it clear that prosperity depended on harmony between gods, king, and people.

By transforming abstract religious ideas into visible, emotional, and participatory events, festivals made theology accessible to everyone. Music, movement, and spectacle communicated authority more effectively than decrees or laws.

In this way, celebration itself became a form of governance—soft power rooted in belief, emotion, and shared experience.

A Civilization That Celebrated Life

Unlike cultures centered on fear of divine punishment, ancient Egypt embraced life, beauty, balance, and joy as sacred values. Even funerary festivals were filled with music and feasting, reflecting the belief that death was a transition rather than an end.

Festivals were moments when:

- The gods were believed to walk among humans

- Past, present, and future converged

- Chaos was symbolically pushed back

- Cosmic order (Ma’at) was renewed

Celebration was not escapism—it was cosmic maintenance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) – Ancient Egyptian Festivals

What was the purpose of festivals in ancient Egypt?

Festivals in ancient Egypt served multiple purposes at once. Religiously, they were meant to honor the gods and renew Ma’at, the cosmic order. Politically, they reinforced the divine authority of the pharaoh. Socially, they united communities through shared celebration, music, food, and ritual. Egyptians believed that without festivals, harmony between gods, humans, and nature would collapse.

How often did ancient Egyptians celebrate festivals?

In certain historical periods, ancient Egypt observed more than 200 festival days per year. This means that celebrations were not rare events but a constant presence in everyday life. Some festivals lasted a single day, while others extended for weeks, involving large segments of the population.

Who participated in ancient Egyptian festivals?

Participation was remarkably inclusive. While priests and the pharaoh played central ritual roles, ordinary people—farmers, artisans, merchants, women, and children—actively took part. Festivals were public events where social divisions were temporarily softened in favor of communal joy and shared belief.

What were the most important festivals in ancient Egypt?

Some of the most significant festivals included:

- Wepet Renpet (Egyptian New Year Festival)

- The Opet Festival (renewal of royal authority)

- The Heb-Sed Festival (royal rejuvenation)

- The Nile Inundation Festival (Wafā’ al-Nil)

- The Festival of Bastet (joy, music, and social unity)

- The Beautiful Feast of the Valley

Each festival reflected a different aspect of Egyptian religion, politics, and daily life.

Why was the Nile central to so many Egyptian festivals?

The Nile was the foundation of Egyptian survival. Its annual flooding ensured fertile soil, agricultural abundance, and economic stability. Egyptians viewed the Nile as a divine gift, so festivals connected to the river were acts of gratitude and prayers for balance—never too little water, never too much.

What role did temples play during festivals?

Temples functioned as organizational centers. Beyond religious ceremonies, they managed food distribution, coordinated musicians and performers, scheduled ritual calendars, and hosted large public gatherings. During festivals, temples became hubs of both sacred and social life.

How do we know about ancient Egyptian festivals today?

Our knowledge comes from multiple sources:

- Temple reliefs and inscriptions (Karnak, Luxor, Edfu, Dendera, Saqqara)

- Tomb paintings showing banquets, music, and dancing

- Religious texts and festival calendars

- Accounts by classical authors such as Herodotus

Together, these sources provide a detailed and reliable picture of how festivals were celebrated.

Did ancient Egyptian festivals include music and dance?

Yes—music and dance were essential elements. Instruments such as harps, flutes, drums, and sistrums were widely used. Dance expressed joy, renewal, and divine presence. In festivals like that of Bastet, music and movement were central acts of worship.

Were festivals only religious, or also political?

They were both. Festivals reinforced religious beliefs while simultaneously serving political goals. By publicly associating the pharaoh with divine favor and cosmic order, festivals strengthened loyalty and legitimized royal power in a way that laws alone could not.

Do any ancient Egyptian festivals still exist today?

While the original religious rituals no longer survive, their cultural spirit endures. Modern celebrations such as Sham el-Nessim and symbolic observances of Wafā’ al-Nil preserve ancient themes of renewal, fertility, nature, and communal joy—showing remarkable continuity across thousands of years.

Why were festivals so important to eski Mısır identity?

Because festivals made belief visible. They transformed abstract theology into lived experience through sound, movement, food, and emotion. For ancient Egyptians, celebrating was not entertainment—it was a sacred duty that sustained life, order, and the universe itself.

Conclusion: Festivals of the Pharaohs

The festivals of the pharaohs reveal a civilization that understood celebration as a sacred responsibility. Through music, dance, ritual, and communal joy, the ancient Egyptians believed they were actively renewing the universe year after year.

Although temples have fallen silent and the gods no longer sail the Nile in golden barques, the spirit of these festivals endures. In modern holidays, public feasts, river celebrations, and New Year rituals, echoes of Pharaonic Egypt still resonate—quietly reminding us that joy, balance, and unity were once seen as divine duties.

Yorum yap (0)